Cubo-Weirdism as psychological and cultural critique

Chris Simonite is a contemporary Canadian painter whose practice combines cultural critique, satire, and environmental reflection. Although trained in multiple media, his creative energy now centers on painting, which he uses to tackle the contradictions of contemporary life. His distinctive style, which he calls Cubo-Weirdism, takes inspiration from George Condo’s “Psychological Cubism” and applies it to portraits, landscapes, and even ecological subjects. For Simonite, Cubo-Weirdism is not just a visual strategy but a way of asking questions: what happens when public personas are fractured, when masculinity is satirized, or when animals stare back at humans demanding accountability for climate destruction?

Cubo-Weirdism defines Simonite’s creative identity. Borrowing from cubist traditions, he distorts, fractures, and rearranges forms in order to expose the psychological realities beneath surface appearances. Where Condo painted imagined faces to explore inner states, Simonite applies this strategy to recognizable figures from popular culture and politics. Their warped features suggest not only their own mental states but also the anxieties projected onto them by society. By exaggerating these distortions, Simonite creates humor tinged with unease, a mixture that provokes audiences to reconsider how collective psychology shapes cultural icons. His humor is rarely lighthearted alone; it is satire that cuts deeper, exposing how culture constructs ideals and contradictions.

Climate change and animals as unsettling witnesses

In recent years, Simonite has expanded Cubo-Weirdism beyond portraits of cultural figures to include animals as central subjects. Painted in uncanny landscapes, they often lock eyes with viewers, becoming symbolic witnesses to ecological damage. Their expressions, anthropomorphic yet natural, ask unspoken questions: what are you doing to our home? This theme reached a peak in his exhibition Hinterland WTF?, where animals were inspired by wildlife cameras capturing unguarded moments of direct confrontation.

By pairing Cubo-Weirdism’s distortions with climate urgency, Simonite created works that were humorous, strange, and unsettlingly serious at the same time. The title itself underscored the animals’ incredulous gaze, presenting climate change as a question no one can escape. Unlike much environmental art that relies on shock or despair, Simonite’s approach uses satire to spark emotional connection, believing that affection for what remains is a stronger motivator than fear of what is lost.

Masculinity and satire as recurring themes

Alongside climate concerns, Simonite continues to explore modern masculinity, a theme that surfaced strongly during his MFA. His satirical works mocked the rigid expectations of the so-called “real man,” showing how cultural ideals of strength and dominance are fragile, contradictory, and often absurd. By poking fun at these expectations, Simonite highlights how masculinity shapes identity in ways both limiting and destructive.

Yet satire in this area is not without risk; audiences sometimes misinterpret critique as endorsement, an ambiguity Simonite acknowledges but embraces. For him, satire is a tool to unravel cultural assumptions, even if it generates discomfort. He sees value in confronting masculinity precisely because it remains unresolved and culturally fraught, making it an essential subject for ongoing exploration.

Press enter or click to view image in full size

By Chris Simonite, The Pretty People

Humor, misinformation, and audience reception

Humor lies at the center of Simonite’s politically engaged practice. His paintings often provoke laughter through their exaggerated forms and playful distortions, but the humor is always a vehicle for critique. By laughing, viewers lower their defenses, making it possible to confront issues like climate destruction, misinformation, and gender expectations without retreating into denial.

Simonite observes that audiences today are more aware of these issues than ever, but they are also vulnerable to manipulation through social media. His work does not attempt to provide definitive answers. Instead, it aims to cultivate curiosity and critical reflection, urging viewers to ask questions about both cultural narratives and their own roles within them.

Sustainability in practice and the role of institutions

Simonite’s studio methods reinforce his themes of responsibility and reflection. He works primarily in oil but has eliminated solvents entirely, a choice made for both health and environmental reasons. This solvent-free approach demonstrates that sustainability can be integrated directly into the creative process, not just addressed thematically. While he admits his exhibition strategies are still evolving, his material decisions already align practice with ecological values.

Beyond the studio, Simonite critiques the limited support structures for Canadian painters compared to European counterparts, particularly the Netherlands. He believes governments and cultural institutions should expand financial and structural support, perhaps through models like Universal Basic Income, allowing artists to focus less on survival and more on creating work that challenges audiences to engage with pressing issues.

Dialogue as the ultimate goal of painting

Simonite insists that painting cannot solve political crises or halt climate change, but it can act as a catalyst for dialogue. His works are invitations to think differently, to notice contradictions, and to reconsider familiar subjects from unsettling perspectives. Whether through a fractured cultural portrait, a satirical take on masculinity, or an accusatory animal gaze, his goal is to start conversations that might not otherwise occur. If a painting makes a viewer research the science of climate change, or simply question a cultural stereotype, then for Simonite the work has succeeded.

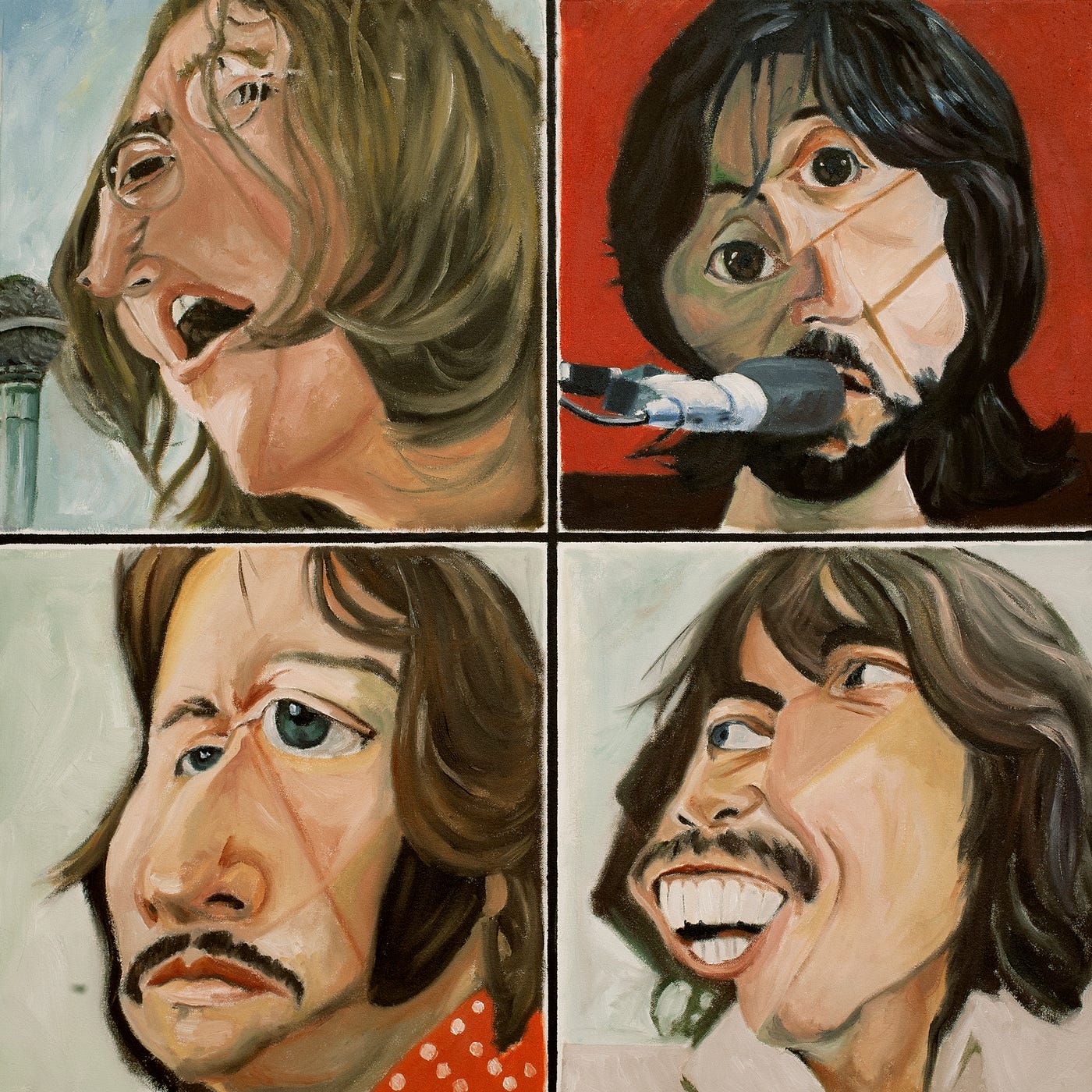

Press enter or click to view image in full size

By Chris Simonite, Get Back

Closing reflections on vision and resilience

Looking back, Simonite recalls advice from a professor who told him, “no one is going to help you.” He interprets this as both a warning and a challenge: young painters should not wait for validation, but they should also recognize that networks of support do exist. His guidance to emerging creatives is to remain authentic, resilient, and skeptical of trends that dilute personal vision. For Simonite, Cubo-Weirdism is more than a style — it is a philosophy of questioning. His paintings are not declarations of certainty but provocations toward reflection.

By blending satire, empathy, and urgency, Simonite creates a body of work that challenges culture while sustaining connection to the fragile environments we share. His solvent-free practice grounds that vision in action, demonstrating that responsibility begins in the studio. Ultimately, his contribution is not to provide solutions but to insist that the most powerful gestures come through reflection and conversation, where culture, identity, and climate intersect.